Nadia Waheed Society as a whole views women as a means to an end

Pakistani-American artist Nadia Waheed insists her nude paintings of South Asian women aren’t about body politics. But talking about them brings up topics of race, beauty standards, and body hair. Writer Alix-Rose Cowie speaks to Nadia about what it means to be a woman in a culture whose highest praise is “good Pakistani girl.”

When Pakistani-American artist Nadia Waheed was at art school in Chicago, a fellow student asked her during a critique why she was drawing white people. She replied that her figures had no race. It was then that she realised that, in western spaces, a “raceless” figure will almost always be interpreted as white.

Blue Portrait (Sisyphus’ Boulder)

Mountain Climbers

In response, she pointedly began drawing unmistakably brown bodies. But she couldn’t shake a feeling of frustration and began to ask herself, “Why do I have to paint them brown to be brown?” “I was honestly, probably childishly, annoyed that I couldn’t draw or paint a body that in my mind was brown and have it be interpreted as such,” she says. “I felt like white and light tones didn’t belong to me (line drawings on white paper read as white figures), and neither did black and very dark shades, because the figure would be incorrectly interpreted as black.”

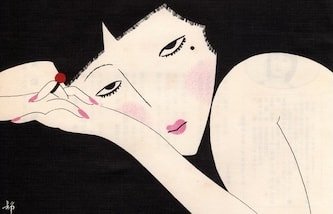

Instead, she broke out of the confines of conventional skin tones altogether and today she paints South Asian women in brilliant hues of green, pink, red, yellow or blue. Where their skin stretches over bone along their knuckles, clavicles or jaw lines, she’s free to use contrasting colors – a yellow streak against pink; orange against green – to highlight these curves.

In each place the rules for girls were different to the ones given to boys.

Nadia was born in Saudi Arabia but spent her early life in cities as diverse as Islamabad, Paris, Cairo and parts of the US. Each new place came with a different set of rules for being a girl; but in each place those rules were different to the ones given to boys. From a young age she became acutely aware that different values and ideals were taught to each gender. The question, “what does it mean to be a woman?” is one she’s had since childhood, and one she explores through her paintings of women.

“The sum of my human experiences thus far have led me to the conclusion that society as a whole views women as a means to an end,” she says. “A wife designed to serve, a mother designed to sacrifice everything for her children, a daughter designed to marry a good son of a good family, a woman designed to be entirely selfless – thinking only of others and never of herself, and in many cases, whom you can abuse verbally, physically, sexually, emotionally with no recourse.”

She rejects this idea. In Nadia’s paintings, the women are centred. They have no dependents other than themselves; they are nobody’s mother and nobody’s wife. They are self-serving and self-soothing. And they contain multitudes. When there’s more than one woman in a painting, the different entities represent the inner selves of the same person in communion with each other.

As the very essence of themselves, Nadia’s women appear nude or in their underwear. It’s an artistic choice that’s at odds with the way she was brought up in a culture that upholds chastity and modesty. “I was told ‘good’ Pakistani girls don’t wear bikinis, don’t talk to boys, don’t wear this type of clothing, don’t say those kinds of words, don’t pose this way in photos, never have sex or speak about sex,” she says. “Otherwise you’re one of ‘those types of girls’: shameless, immoral, poor reflections of their parents, with poor values. They’re sluts, whores, bitches, and every bad thing that happens to them is met with a shrug of the shoulders and a “well, she’s that type of girl.”

“The nudity is a symbol for my fundamental acceptance of myself as I am and the decisions I made to get to this point: the clothes I wore, the people I slept with, the rules I broke and the damning mistakes I made.”

Nadia paints from no reference other than her own body. When she’s unsure of how to draw a curving torso or a folded limb, she feels the position out herself and then draws from her own image. The women in her paintings are strikingly beautiful, but beauty’s not something she sets out to capture. Her intention is to portray South Asian features: thick brows, high cheekbones, almond eyes and full lips. “If my women are beautiful it’s probably because South Asian women predominantly are beautiful,” she says. “Western culture has conditioned us to believe we’re not, but we are, we’re a pretty good looking bunch of people if I do say so myself. And I do, I do say so,” she laughs.

The nudity is a symbol for my fundamental acceptance of myself, as I am.

Moksha

Gender Reveal

For women everywhere, hair is intertwined with identity. It’s both political and deeply personal. Nadia uses it in various ways as a weighted symbol. A thick, shining braid is a symbol of traditional beauty in Pakistan. In Nadia’s paintings her women wear long braids as a signifier of their culture, or they boldly chop them off in an act of defiance. “In Rite of Passage the posture is victorious but the turned head meant that maybe it’s not exactly what she wanted, or maybe she felt the pain that came with the disconnection,” Nadia explains. “In Moksha the figure is looking at us directly, cut braid in hand, saying “I cut this but I decide when to let go.” Her way of holding onto both worlds.” In Gender Reveal, the hair of the two women is braided together to represent “a bond that even if broken can be remade again, infinitely,” Nadia says.

But she’s been surprised to find that her women’s plaits aren’t the hair that she’s asked about most. “I didn’t realize that pubic hair was this much of a statement!” she says. What began as a simple personal preference has become a hot topic that she’s growing strong opinions on through being confronted with people’s curiosity. “We all grow pubic hair. I find it shocking that the majority of women remove the entirety of their hair,” she says. “Then again, we live in a society that infantilizes women. At the end of the day every woman is free to do what she wants to, whatever makes her feel most like herself. I guess my women, like myself, feel most themselves with pubic hair.”

Sharing her works on Instagram has seen Nadia temporarily banned on the platform twice. She suggests that it might just be an algorithm glitch. “That being said I do get a fair number of messages from South Asian people telling me to put clothes on them, that I’m shameless, a whore painting whores etc.” In spite of this, she remains a champion for women’s autonomy, for those types of girls.

“I hear stories about them,” Nadia says, “girls caught between two value systems who question what is really best for them and who are brave enough to make the decisions and mistakes they need to make to become themselves, to live their one and only life, and I accept them. I give them worth and value and respect.”